Visitors to Winchester Cathedral have long strained their necks to look up at the six mortuary chests, containing the remains of our Saxon royal family

The mortuary boxes have been absent for a little while whilst conservation work is undertaken, at the same time archaeologists will take the opportunity to use DNA analysis to try and discover whose remains are actually in the boxes.

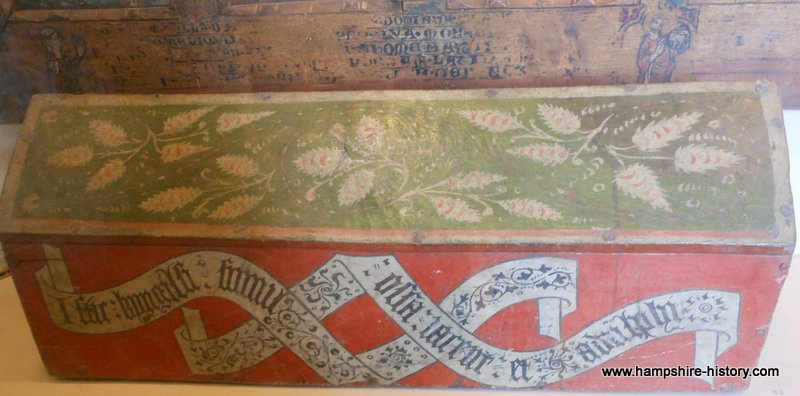

The remains of the kings, queens and prelates were removed from their original burial place, the crypt in the Old Minster and placed in lead lined coffins in the new Norman cathedral. This was not to be their final resting place though. During the Renaissance period in about 1525, the remains were moved once more and placed in the specially constructed mortuary chests we see today and placed high up on top of Bishop Fox’s stone screens on each side of the presbytery. Originally there were eight chests but these were not the first chests, when opened for examination in Victorian times, earlier boxes were found inside.

To whom do the remains belong?

Winchester is fortunate to have been the burial place for some of England’s earliest monarchs and the remains are thought to be those of;

King Cynegils who reigned from 611 – 643AD

King Cenwalh who reigned from 643 – 672AD

King Egbert who reigned from 802 – 839AD

King Ethelwulf who reigned from 839 – 859AD

King Cnut who reigned from 1016 – 1035AD and his wife Emma who died in 1052 and possibly their son Hathercanute.

Finally three bishops, Bishop Wine, bishop from 662 – 663AD, Bishop Alwine 1032 – 1047 and the last Saxon bishop, Bishop Stigand 1047 – 1070AD

The Background to the boxes

The boxes themselves were created during the Renaissance period, made in about 1525 with the names of each person painted onto them. They remained in their new position until the 14th December 1642, when during the English Civil War, Winchester was subjected to a violent attack by the Roundheads, during which time they ran amok throughout the cathedral. The mortuary chests were broken open and the remains scattered. Following the attack the remains were gathered together and placed back into six of the boxes. They were of course muddled up by then with no way of knowing which bones were which. Years later in 1661, an inscription was added to one of the boxes, explaining that the bones of princes and prelates had been promiscuously laid together after being scattered by sacrilegious barbarism in 1642.

The Next Chapter

A few years ago preliminary research was begun on the boxes and the remains. They have been removed to the Lady Chapel for examination, kept behind a screen but remaining on consecrated ground, archaeologists are working to see if DNA can help identify the remains. Following the success of the discovery of King Richard III’s remains and the attempt to verify King Alfred’s in Winchester only recently, work has begun to identify those of King Cnut. It will be interesting to see if the work done on the bone in the Winchester Museum can help with the project.