The Waltham Blacks driven by social injustice?

In the early decades of the 18th century, many people in England, having enjoyed a relative economic boom, found themselves in a state of poverty and existing in an increasingly unequal society.

The ‘Blacks,’ were groups of men, who, acting out of a sense of social injustice, decided to carry out poaching and raiding activities, on lands belonging to the wealthy. They blacked their faces to avoid recognition and in a well orchestrated way, set about poaching deer and other game. There were two main groups, one in Hampshire operating out of Waltham Chase and the other from Windsor.

Poaching the Bishop’s lands.

In October 1721, sixteen poachers assembled themselves in Farnham to poach the Bishop of Winchesters lands. Deer were taken and killed. Four of the poachers, their faces blackened to prevent identification, were caught and sentenced. The poachers came back and in a calculated manner, that was a conspicuous social statement, signalling much more than just poaching for the pot, they attacked the Bishop’s lands again, taking and killing more deer.

A clear message was being sent from a section of society who were full of resentment at the draconian game and forest laws which were making life very difficult for non land owning classes in Britain. The exploits of these Hampshire outlaw groups spread, with further gangs establishing themselves in Windsor Forest and around London. The Hampshire groups though, ‘upped the game’ and stole a shipment of the King’s wine, things were about to become increasingly difficult for these groups of outlaws.

What motivated them to carry out these criminal acts?

We need to look back into English history to understand more about land ownership to understand the motives of these 18th century outlaws. Prior to 1066, life in England was lived in little villages which were, almost completely self-sufficient and self-supporting. Villages were separated from each other by miles and miles of thick forest and heath land with tracks, winding through the thickets and woodland. These tracks sometimes joined up with a road, built by the Romans some six hundred years earlier but in the main settlements were quite isolated from one another. Life was, essentially one of survival but for most, there was plenty to eat and drink. There was space and virgin land which ambitious people could clear and cultivate. The struggle of day to day living was, in general hard and defined by quite narrow, geographic limits.

The wild forests and heathlands

A village was usually surrounded by a fence and its land by another, outer fence. This was intended to keep domesticated animals in and wild ones out. Beyond the confines of the village were miles and miles of thick forest and heath. These were wild empty places where men would venture by day, to herd their pigs or gather logs and wild herbs but most would not willingly spend the night there, for fear of wolves and spirits.

There was little movement of people around the country

It’s difficult for us to imagine not travelling any distance from where we live but essentially in pre – Norman England, few ordinary people made journeys, short or long. Journeys were dangerous, not necessarily from the point of view of human attack but from accident, sickness or getting lost. Strangers meeting each other would hail or sound a horn to alert others of their presence and that they travelled in peace.

But following the Norman Conquest of 1066, the emergence of a new community of people emerged, outlaws, who lived in the great forests of Hampshire and beyond.

England was left shattered by the conquest of her lands and her people struggled to cope under the new order. Many of them lost all their property and rights to hunt and gather. Forced to the margins, many turned to crime, hiding themselves and their activities in the forests and becoming outlaws. The villages and common lands that had supported them, were appropriated when William the Conqueror sought to forest as much of his newly acquired land as he could, creating royal hunting grounds and warrens. The resulting forests flourished and hundreds of years later, Hampshire was covered by great tracts of forests and chases. Waltham Chase, the New Forest, Woolmer Forest, Forest of Bere and Alice Holt to name but a few and out of one of these forests, emerged a group of outlaws who became known as the Waltham Blacks.

The emergence of the outlaw, as a sub class of society, had begun.

Times of hardship has always driven some to crime. Economic boom for some, was usually followed by a time of bust for others. The economic collapse that followed the disaster of the South Sea Company investments, affected people up and down the country. In the early 1700’s, Britain had been riding a wave of economic prosperity. A large section of the population had money to invest, so the South Sea Company had no problem attracting investors. Deals were done and the boom seemed unstoppable but then the bubble burst, leaving many destitute. The knock on effect filtered its way down to the poorest in society and out of this desperate situation, emerged the Waltham Blacks. In order to avoid starvation, the poor needed to be able to take game but the crippling ‘game laws’ and ‘forest laws’, which forbade anyone from hunting or selling game, prevented this. Those caught in the collapse and its aftermath, from the poor to the not so poor were stirred to action. Groups of ‘outlaws’ formed intent on drawing attention, by direct action, on the unfairness that existed in society.

Poaching the Bishop’s lands.

In October 1721, sixteen poachers assembled themselves in Farnham, to poach the Bishop of Winchester’s land. Deer were taken and killed and four of the poachers, their faces blackened to prevent identification, were caught and sentenced. The poachers however were determined to show the strength of their anger and returned to the Bishop’s land, to take more deer. Their action was calculated and determined, a conspicuous act of criminal behaviour, to draw attention to the injustice of the English game laws.

A clear message was being sent from a section of society who were full of resentment at the draconian laws. The exploits of the Waltham Blacks and other Hampshire groups spread. Poaching gangs established themselves in Windsor Forest and around London. The Hampshire group however took their action one step further and took not just the Bishop’s deer but stole a shipment of the King’s wine as well.

The Black Act

Such insurgence could not be tolerated by those in power. Any hint of political unrest that threatened the land owning classes, resulted in swift action and this was no different.

In response to the gangs, the government introduced the Black Act, it came into force on 27th May 1723.

Put in place to combat the rise in game poaching, this act merely served to sharpen the conflict. It added nearly fifty capital offences to the rolls and was the law that was at the heart of the 18th century, ‘Bloody Code’.

The pursuit of game was for the privileged few only, farmers were not allowed to take game from their land, although the rich on their huge estates were allowed to trample the farmer’s crops to pursue it. Poaching was the result and as the conflict intensified, the practice of the poachers blackening their faces to avoid recognition, served to antagonize the higher echelons of society even further.

The Black Act made it a hanging crime to go on a hunt in disguise, to poach deer, rabbit or fish. You would be put to death for damaging orchards, gardens or cattle. Whether you committed these crimes or conspired to do so, if found guilty you would be put to death.

So named because it targeted poachers’ practice of “blackening” their faces, the new law made it a hanging crime to go on the hunt in disguise, as well as a hanging crime to poach deer, rabbits, conies, or fish. Formerly, “deer-stealing” and the like had been mere misdemeanors.

The seven Waltham Blacks

The capturing of the Waltham Blacks was a violent scene, during which, a murder was committed. The seven ‘Blacks’ were confronted by a group of keepers and during the skirmish that occurred, one of the keepers was murdered. The seven men were Richard Parvin, Edward Elliot, Robert Kingshell, Henry Marshall, John and Edward Pink (an old Hampshire surname), carters from Portsmouth and James Ansell, alias Stephen Phillips. They weren’t all taken at once, some escaped but were later apprehended.

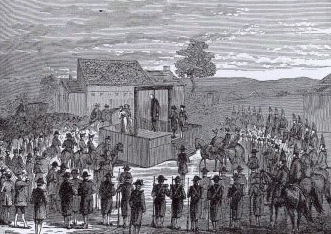

The seven were sent to Winchester Gaol but to show the general population that the Government meant business, they sent the seven Waltham Blacks to London to be tried, away from their sympathetic communities, who themselves were suffering from the draconian laws. Henry Marshall was guilty of the murder, along with Robert Kingshell. The seven men were found guilty and sent to be hung.

The trial though, brought out more about the community that made up the ‘Blacks’ than had been known of before. Richard Parvin, an alehouse keeper from Portsmouth, protested his innocence to the end, claiming he was on other business in the forest, went into another alehouse in the forest, here the inn keeper identified him as being part of the gang of outlaws. Edward Elliott, a young lad of seventeen, appears to have initially been coerced to join the group. There appear to have been certain ceremonies and oaths undertaken. He was told he had been enlisted into the service of the ‘King of the Blacks’ and that failure to obey orders or to break his oaths, would result in them using their magical powers and turn him forever into an animal. It seems they held people to them by using terror, threatening them in all sorts of ways, including death. None saw the taking of deer as an offence. As far as they were concerned, the deer were wild beasts and as such, the poor man had the same right to them as the rich. They shared out and ate the deer together. It is said that they were incoherent with terror when brought to the hanging. The Black Act had the desired effect though and within a year the organization, if that is what it was, had melted away.